Intro to Knife Skills: The Chef's Knife

To be honest, I was not prepared for the copious abundance information I would find on this topic. I originally planned to make this single big-ish, totally comprehensive, all-inclusive knife know-how intensive with helpful tidbits and minimal wordiness. Then I started researching. I discovered things I thought to be truths to be completely wrong, lots of new info, and factoids I honestly just don’t have the space to include. So, I have decided to break this guy up into chunks. The first part of this series being knife types, their jobs, and semi-useful trivia (that may of may not win you a free beer somewhere down the line) and the second part explaining knife cuts and knife care.

So, buckle up kids, it’s gonna be a road trip. One with minimal bathroom breaks eventually leading to snacks…hopefully.

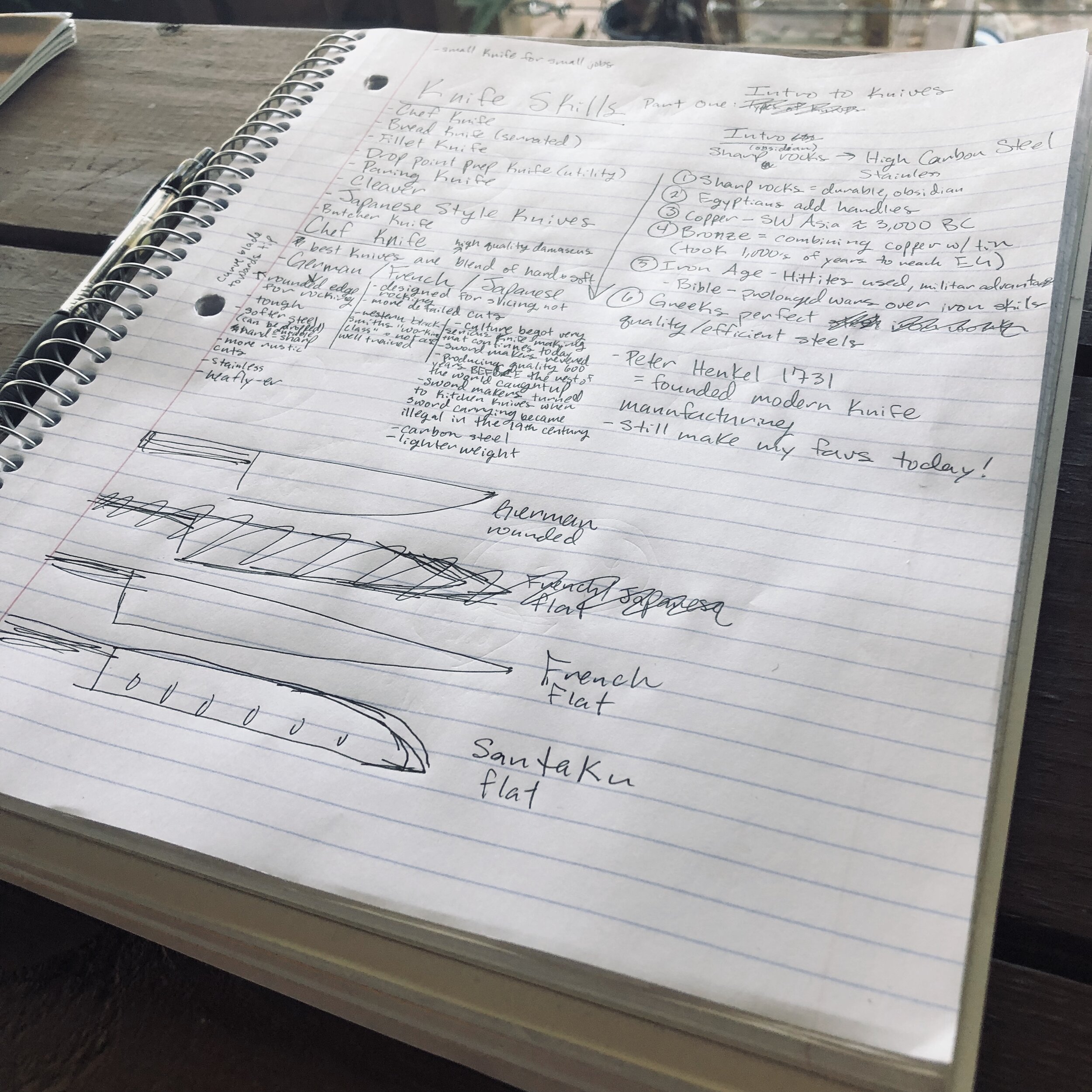

My research for this blog

Blades: A History

So how did we go from sharp rocks to high carbon & stainless-steel creations that can cost as much as a car? (Not kidding. this is a thing.

History took a long winding road to get here, folks. Ancient people groups used simple handheld sharp rocks as cutlery for a looooong time. The Aztec, Maya, and early nomadic tribes across the globe used primitive obsidian tools with little to no alteration for centuries. We know at some point the Egyptians added handles and embellishments because, let’s face it, that’s kind of their thing, but no changes

As early as 6,000 B.C. the people of the fertile crescent were smelting copper and putting it to use in tools and weaponry. This technology, like many subsequent advancements, was spread through death, destruction, and war. The guy with the most effective weapon nearly always wins, with few exceptions. The enslaved victims then made said weapons for future wars, learning the techniques, driving the war machine, and so history goes.

Asians began mixing copper and tin together to create bronze sometime around 3,000 B.C., thousands of years before the Europeans, beginning the Bronze age. Moving into the iron age, blades were made stronger with the new material, but brittle, and no more efficient to make, until the Greeks & Japanese really began to perfect the art of blade-making by mixing super hard and flexible metals together to create balance, and eventually one of the most revered blades the world over: the katana.

From here, sword smithing and knife making become increasingly different depending on where in the world you are. Japanese sword makers have a cult-like mentality with ceremonial clothes to be worn, prayers said, and intensive study and apprenticeship to be completed before anyone could claim the revered title of Master. Whereas in Europe, blacksmiths were an important piece of civilization, but they were working class. They were the blue collar, soot-covered working men compared to their white robe wearing, ceremonially washed Japanese counterparts. And in the 19th century, when carrying a sword became illegal in Japan, these prestigious master blade makers needed a new market for their craftsmanship. They found their new clients in chefs hungry for quality knives…pun intended.

As far as knives for culinary use were concerned, the Japanese had the craftsman market cornered until a man named Peter Henkel (sound familiar?) came along and set the precedent for modern knife manufacturing in 1731. Henckels knives are still made today and revered for their quality and tough, German durability. They also happen to be my personal favorites.

Enter the Chef Knife

The Chef’s knife is the darling of kitchen cutlery. The best ones are babied and passed down like heirlooms. Quality knives are forged from either high carbon or stainless steel, each of which have benefits and drawbacks. Stainless steel is less maintenance but doesn’t patina the way high carbon steel does. And since they are made of a much harder metal, they hold an edge longer than stainless steel. But high carbon knives are brittle and require a delicate hand since the harder the metal, the easier it is to break under stress. Think of a twig: what is easier to snap in half? A dry, hard branch, or new green wood with lots of water?

Henckels knives are almost always made with stainless steel, making them the perfect knife for foodies and home cooks. The flexible structure of stainless steel allows this knife to be man-handled and dropped without breaking. They do not, however, hold a sharp edge nearly as long as expensive high carbon blades. I have personally only ever owned stainless steel knives, and can speak to their durability, but they have to be sharpened All. The. Time.

Henckels typically uses the full-tang, stainless steel design in their blades, while Japanese knives (as in the ones actually made in Japan) are nearly always made with high carbon steel & hidden tang design. The tang is the part of the blade that extends into the handle. Full tang means the metal part of the knife continues all the way through the length of the handle and is riveted between two “scales” (pieces of wood or other handle material). Hidden tang is when the knife maker inserts the tang into a solid handle either by burning it in or drilling a hole. Again, both designs have unique benefits: full tang is more controllable, but less artistic, where the hidden tang puts the balance of the blade more forward (allowing for a finer slice), but the handle can be ground down farther and create a more custom feel in the hand.

The above pictured Henckels knife is a full tang blade. Notice the rivets? Most western style kitchen knives are made this way, where Japanese knives tend to be hidden tang.

Also pictured are different styles of knives: The Japanese Santoku, French, & German style blades. These shapes are all considered chef knives, and may seem similar, but could not be more different. Firstly, two of these examples are made of Damascus steel, which is high carbon steel that has been folded over and over to create lamination (different colored lines) in the finished knife. This method produces a blade with both flexibility and strength. Damascus Steel is metal puff pastry. The Henckels knife is made of stainless steel.

Each of the three examples is made in a shape unique to its nominal country of origin. German style knives have blades that curve towards the tip to facilitate a rocking motion for chopping. If you’ve ever watched Rachel Ray cook, this “rustic” chopping style is typically how she rolls. You start with the point of the knife on the board and rock the blade back towards the handle. This method produces a rustic chop that is perfectly suitable for most everyday cooking needs like chopping onions or making a mince of any kind.

French & Japanese style knives have a straight edge which either gradually meet the tip at an acute angle (in the case of the French style) or the tip itself is dropped to meet the edge (Japanese, specifically Santoku.) The straight edges on these knives are best for the precise knife cuts required of delicate preparations like sashimi or tournée. But more on knife cuts in a later post, I promise! These two styles developed over time in their respective countries as competitive knife-makers tried to one-up each other. Therefore, they tend to be similar. The cuisine they are each used for also tends to require more delicate knife cuts. I mean, I mean, try to imagine sushi without dainty portions of perfectly sliced fish perched on rice? Not quite the same, really. Or a tarte tain without rings of apples cut to precisely the same shape? It’s so un-French, it’s basically American.

So, if you came to this article looking for answers, I hope maybe you found a few.

Until next time, keep cooking, and keeping dreaming.

-Nicki